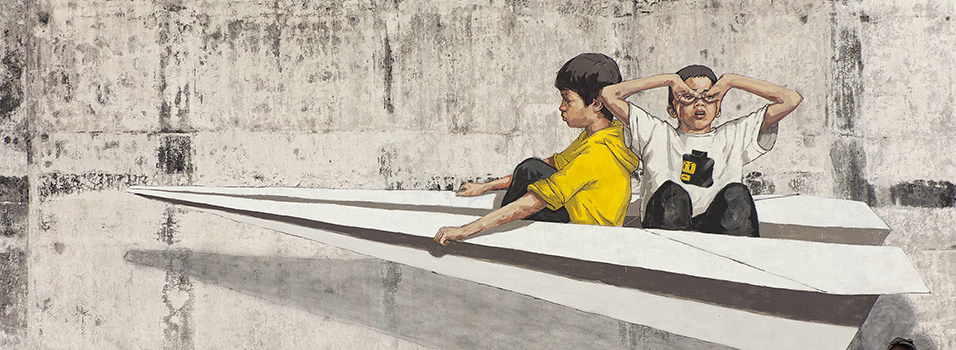

The good, bad and ugly of street artist Ernest Zacharevic's murals

Ernest Zacharevic’s street art has become synonymous with Penang, especially in George Town, where his murals are not only admired but have also sparked changes in the local community and tourism industry. Known for his murals of children interacting with everyday objects like chairs or bicycles, Zacharevic’s work has become a staple of the city’s tourist trail, sparking a combination of admiration, controversy, and commercialization.

The Good:

-

Impact on Tourism: Zacharevic’s murals have become iconic symbols of Penang, with the "Little Children on a Bicycle" mural becoming a particularly popular image on social media. The power of social media has played a significant role in amplifying the popularity of these artworks, allowing them to reach global audiences and bringing tourists to the city to view the murals in person. The paintings have successfully created a link between art and tourism, bringing visitors from around the world to Penang.

-

Cultural Significance: Zacharevic’s work often plays with the contrasts between old architecture and contemporary street art. By painting on heritage buildings, he creates a juxtaposition between the city’s past and present. This commentary on the rapid urbanization and changes in South East Asia allows locals to reflect on their evolving environment while engaging in something dynamic and visually appealing.

-

Community Engagement: The community has been instrumental in preserving and maintaining Zacharevic’s murals. Locals have actively replaced stolen items (like motorbike parts and chairs) featured in the artworks, demonstrating their sense of ownership and pride in these murals. In some cases, the murals have even been restored by local volunteers, creating a shared responsibility between the artist and the community.

The Bad:

-

Commercialization and Exploitation: The explosion of tourism linked to Zacharevic’s art has led to commercialization in the area. Souvenir shops sell items like magnets, postcards, and T-shirts featuring his artwork. While this brings economic benefits to the region, Zacharevic expresses a concern about the way street art has been exploited for commercial gain. Local businesses are increasingly relying on the artwork to attract visitors, and this reliance on tourism dollars can shift the focus away from the intrinsic value of the art itself.

-

Quality Concerns: As street art becomes more mainstream, there is also concern about its quality. While some see it as an exciting evolution of the urban landscape, others feel that it has become an oversaturated and unchallenged form of expression. Many worry that the influx of street artists coming to Penang may prioritize commercial appeal over artistic integrity, and the murals themselves might not always reflect the true spirit of the city or the local community.

-

Vandalism and Temporary Nature: Another challenge is the temporary nature of street art. Zacharevic acknowledges that street art can be easily vandalized or weathered, and many of his murals have been damaged or stolen over time. While he appreciates the community’s efforts to restore his work, he emphasizes that the essence of street art lies in its impermanence. The act of vandalism and the fading of the artwork contribute to the raw and fleeting character of this medium, which is part of its appeal, but also its challenge.

The Ugly:

-

Tourism-driven Pressure: Zacharevic expresses a conflict between the art’s success in drawing tourists and the pressure this places on the local community and authorities. The rapid commercialization of these murals—along with the influx of tourists and the boom in souvenir sales—can create dissonance between art as cultural expression and art as a tool for profit. This shift is especially apparent when shops or businesses that claim to have a “heritage” connection are more interested in capitalizing on the tourism boom rather than engaging with the true meaning of the artwork.

-

Exploitation of Street Art: Zacharevic’s comment on businesses using street art for their own marketing purposes points to an uncomfortable reality. This exploitation is prevalent in how businesses, including hotels and restaurants, have commissioned murals for their interiors while capitalizing on the aesthetic appeal of urban art. This raises a question about the purpose of street art: is it about self-expression, or is it simply an aesthetic tool for businesses to enhance their branding?

Final Thoughts:

Zacharevic’s work brings together the beauty of local architecture, the energy of street art, and the complex dynamics of tourism and commercialization. While his murals have undoubtedly enriched the urban landscape and become a source of local pride, they have also raised important questions about the balance between artistic integrity, cultural preservation, and economic growth. The good is the newfound appreciation for street art and its power to bring people together, while the bad and ugly lie in how this art is sometimes exploited or undermined by commercialization and vandalism.

For Zacharevic, the true value of his art lies not in its longevity or how it is used, but in the conversations it sparks and the temporary impact it has on the places it inhabits. As he says, “From my point of view, let it fade.”